TRUST THE WOMEN MOTHER AS I HAVE DONE

On this date back in 1911, Australian and New Zealand women were the stars of the remarkable Women's Suffrage Coronation Demonstration in London. Daughters of Freedom who inspired the world.

Even basic rights we now take for granted had to be hard fought for. First posted here two years ago in slightly different form, but worth repeating because its a story that’s still inspiring and perhaps even more relevant than ever.

On 17 June 1911 in London, 40,000 marched in the Women’s Suffrage Coronation Demonstration. It brought together 28 different suffrage organisations and took three hours to pass.

The procession was watched by tens of thousands more, who filled public viewing stands erected in preparation for the coronation of George V just days later.

The Australian and New Zealand contingent were the undoubted stars, cheered all along the route.

In 1902 Australia had been the first nation in the world to give women the vote (though not Aboriginal women). New Zealand had been the first dominion to do so, even earlier, in 1893 - including for Maori.

In the USA women were not enfranchised nationally until 1920, and British women were denied a voice until 1928!

No ragtag crowd, the marchers that day included Margaret Fisher, wife of the Australian Prime Minister; Emily McGowan, wife of the Premier of New South Wales; and Lady Anna Stout, wife of New Zealand’s Chief Justice and former Prime Minster, alongside renowned Australian activist Vida Goldstein.

Australian Daughters of Freedom in the Australian and New Zealand contingent in the great suffrage demonstration of 1911. They received rapturous applause as the procession made its way through the capital’s streets. Images: Sims Dickson Collection and Archive.

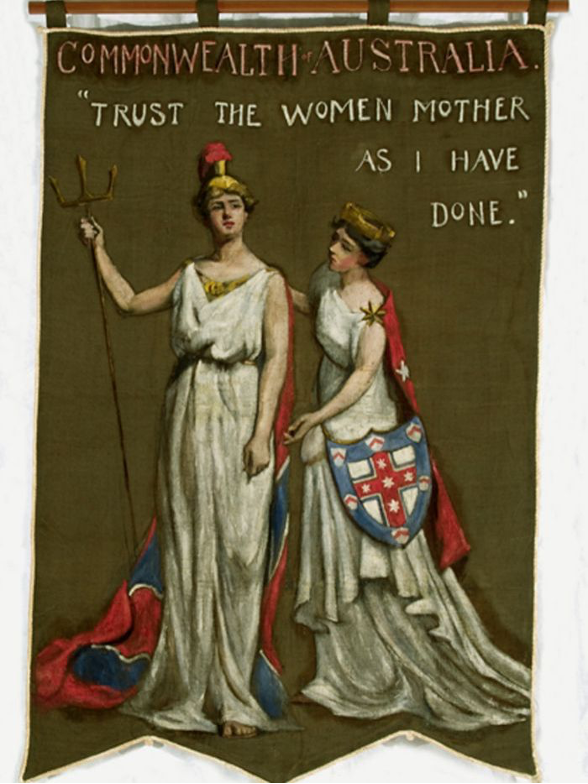

Women from the British Empire’s two furthest outposts marched beneath a banner proclaiming a consciously feminised message: “TRUST THE WOMEN MOTHER AS I HAVE DONE”. Below it was an image that positioned women, not men, as the holders of wisdom and leaders of progressive thought.

Dora Meeson (1869-1955), The Women’s Suffrage Banner, 1908. Parliament House Art Collection, Canberra.

The banner was designed, painted and carried by Australian artist Dora Meeson. It is now on permanent display in Australia’s Parliament House.

Meeson’s painting shows Britannia being addressed by the newly federated Commonwealth of Australia, who urges the mother country to grant British women the same voting rights Australian women had already enjoyed for nearly a decade.

Dora Meeson by her husband George Coates. Probably painted around 1900-1910. Image: Sims Dickson Collection and Archive.

Dora Meeson was a lifelong feminist, a fighter for women’s rights in New Zealand, Australia and the UK, a disrupter a century before the term became fashionable. She was born in Melbourne in 1869, and she was one of Australia’s great political artists. Her legacy remains unrivalled.

Universal suffrage - equal voting rights for women - was the defining marker of the new Australian nation’s identity. It was a battle fought and won by women. As historian Clare Wright puts it, Australian Daughters of Freedom won the vote and inspired the world.

In 1911 Australian and New Zealand women marched in London as leaders, not followers.

Four years later at Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, Australian and New Zealand men were incidental players in a disastrous, ill-conceived military misadventure, under British command.

Almost overnight, the trauma of the losses at Gallipoli, and then the Western Front, displaced women from their position in Australia’s national story. Gallipoli became Australia’s dominant historical narrative, and still is.

History, a fickle barometer at the best of times, failed Dora Meeson.

Meeson’s independence of thought, her activism, her immense commitment to women’s rights, was an inspiration to the band of free-thinking expatriate younger Australian women artists she mentored in bohemian Chelsea1. But her banner, her political drawings and her paintings have defined her as different and separate from those much younger women, who came to be celebrated as inventors of Australian modern art. Dora Meeson rarely figures in the pantheon of great Australian artists.

And in the closing of the Australian mind that occurred in the wake of the Great War, her action-based progressive ideology2 was at odds with the collective shell-shock that descended on the nation. A conservative mindset took hold in which change was viewed with suspicion and rejection.

We’re still living in the shadow of that mindset. It’s bolstered ever stronger by the continuing promotion, by media and government, of the sacrifices of men at Gallipoli as Australia’s defining moment.

Never again would Australia assert an independence of mind on the global stage3. And still today Australian women need to demand what men take for granted: respect, equality and safety.

An apology for a scandalous culture of disrespect and abuse of women within Parliament House itself, the very home of Meeson’s glorious banner, shows how great the need for change.

So more than a century on, let’s at last celebrate Dora Meeson the artist, radical thinker and activist. In doing so we’ll give long overdue respect to the Australian and New Zealand women’s own Anzac moment. An overdue revision of no less than Australia’s dominant historical narrative.

Perhaps in the process we’ll be inspired to remake Australia a fairer, more respectful place. Which, after all, is only what those bold women were hoping for, all those years ago.

Dora Meeson by her husband George Coates. Painted around 1910-1915. Victoria and Albert Museum Collection, London.

Dora Meeson Coates, photographed in 1933. National Portrait Gallery Collection, London.

Recommended further reading:

Clare Wright, You Daughters of Freedom: Australians Who Won the Vote and Inspired the World, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2019.

Myra Scott, How Australia Led the Way: Dora Meeson Coates and British Suffrage, Commonwealth Office of the Status of Women, Canberra, 2003.

For example: I was keeping up my art classes at night and enjoying myself immensely with a rather bohemian crowd of other young people. About this time [1931] I met a wonderful Australian artist and feminist (another first) Dora Meeson-Coates (whose paintings hang in many galleries around the world) who introduced me to the Anzac Fellowship of Women. She kept open house in her studio in Chelsea every Sunday afternoon for struggling impecunious artists; and we could always be sure of a warm welcome with a sandwich and a cup of tea. It was a great boon to very many of us. London on Sunday afternoons in the winter could be a cold and lonely place. From ex-pat Australian art student Kit Carroll-Clark’s memoir of her time in London, 1930-1971, unpublished, (Sims Dickson Collection and Archive).

Beyond her career as an artist and suffrage activist, at the outbreak of war in 1914, and the consequent suspension of suffrage campaigning, Dora Meeson became a founding member of the Women’s Police Volunteers, a group dedicated to upholding the rights of women caught up in the British judicial system. At a time when juries excluded women, and women were not allowed in court rooms during rape trials, for fear their supposedly delicate sensibilities would be offended, the Women Police Volunteers provided support to the victims.

A tragedy that led us into terrible disasters in the early stages of WW2 in Greece, Malaya, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies, atomic bomb tests that led to radioactive poisoning of Aboriginal Australians and their Country, lost wars in Vietnam and Afghanistan, illegal war in Iraq, and a bizarre refusal to acknowledge climate change as an existential threat.