TRANSCENDENCE - a virtual exhibition

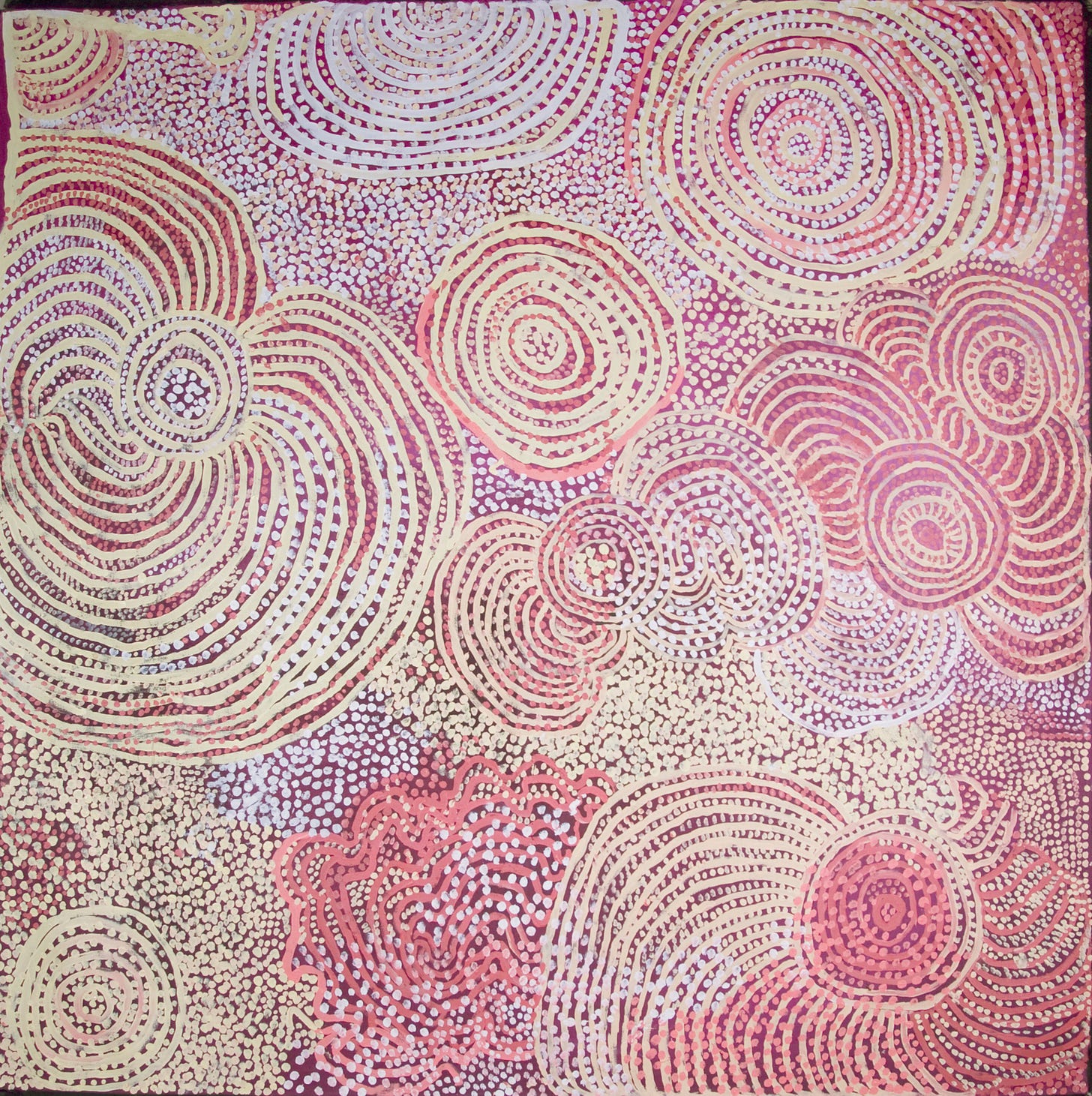

“Transcendent, with awesome majesty", composer John Tavener's instruction to musicians performing The Protecting Veil, offers an illuminating view into the heart of Aboriginal desert art.

When composer John Tavener wrote “Transcendent, with awesome majesty” at the head of his 1987 score The Protecting Veil, he was calling for his musicians to rise to the challenge of the intent implicit in the piece: a composition for solo cello and orchestra in which the cello sings no less than the voice of Mary, mother of God.

Inspired by his interest in, and conversion to, the Russian Orthodox faith, Tavener’s work translates mystical and meditative words, thoughts and actions into musical form. While the notes on the page certainly map Tavener’s intent, their translation into sound – with transcendence and awesome majesty befitting their subject – relies on so much more than simply a correct reading, and mundane adherence to a given tempo or meter – the usual purpose of instructions (for example the familiar adagio for slow, and so on). The composer here demands that the musician must imbue her or his performance with religiosity in such fulsome, unalloyed magnificence that listeners – and indeed the musicians themselves – are taken beyond the normal realm of human experience, into a metaphysical place accessed through the transformative power of music.

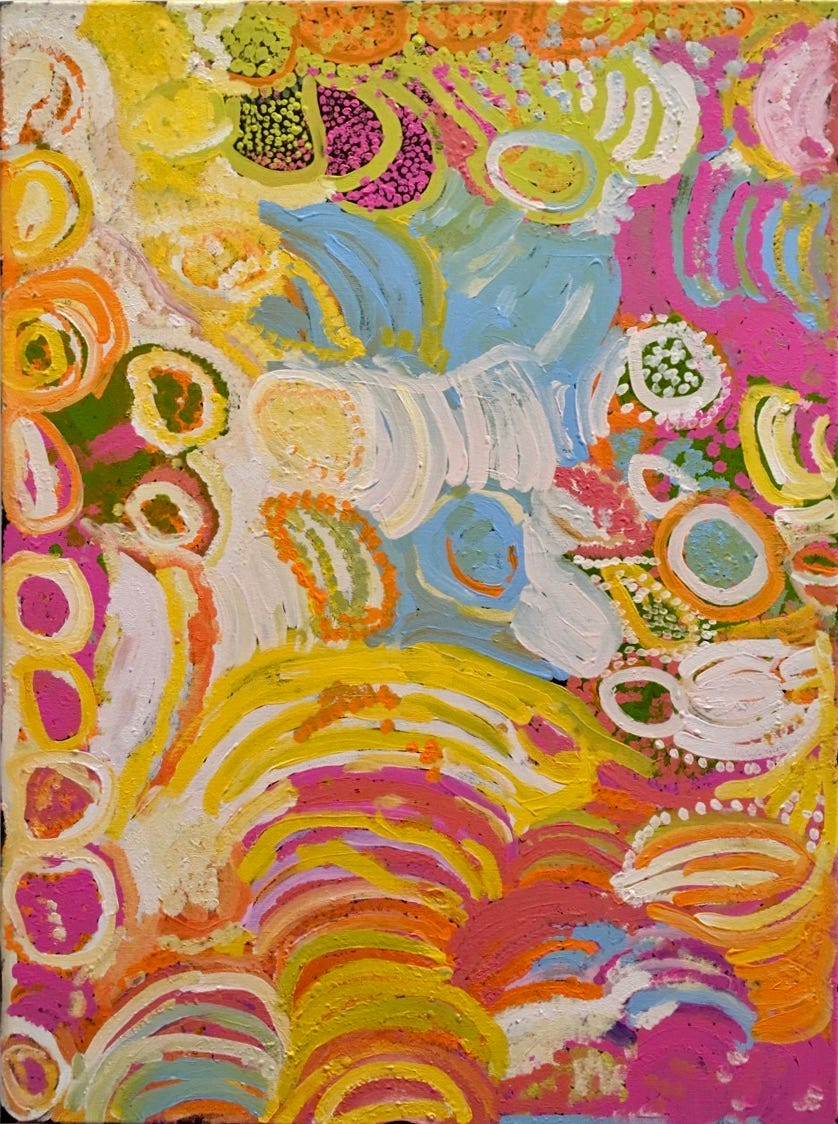

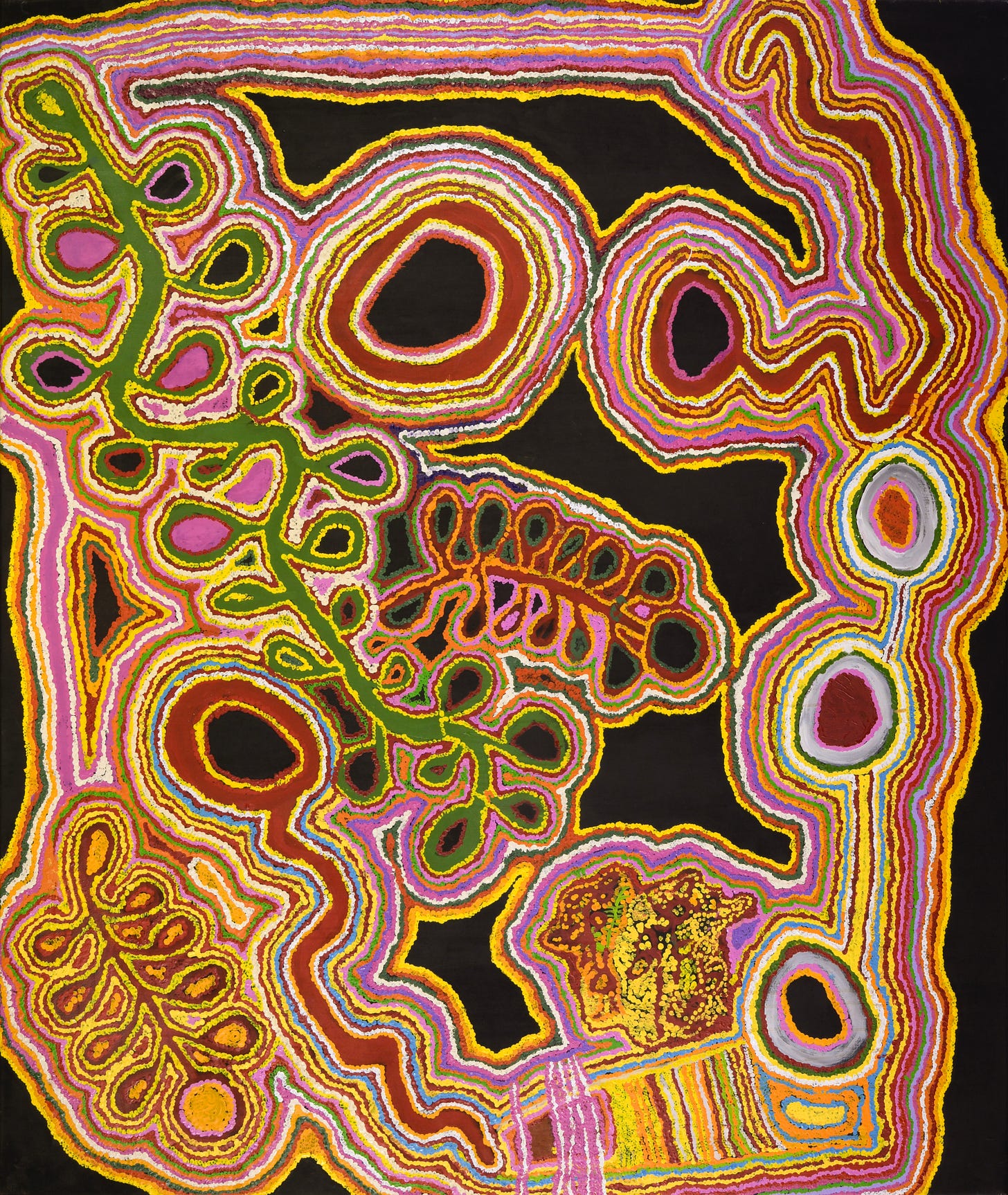

Something similar is going on with these paintings. They push us way beyond our narrow everyday understanding of what, how and why. The banal and the ordinary are banished and we have entered the realm of the universal truth. Great art should demand this as a matter of course, but so often fails to rise to the challenge. Not so these works, selected for the very transcendence and awesome majesty they manifest so clearly.

While it would be absurd to suggest these paintings are in any way derived from a philosophical, religious or historical link to Tavener’s own religious inspiration, there is nonetheless a religious quality in their uniquely Aboriginal mythopoeticism (extroverted ecstasy to use Diana James’s elegant phrase) that even viewers schooled only in the western tradition of art can recognise.

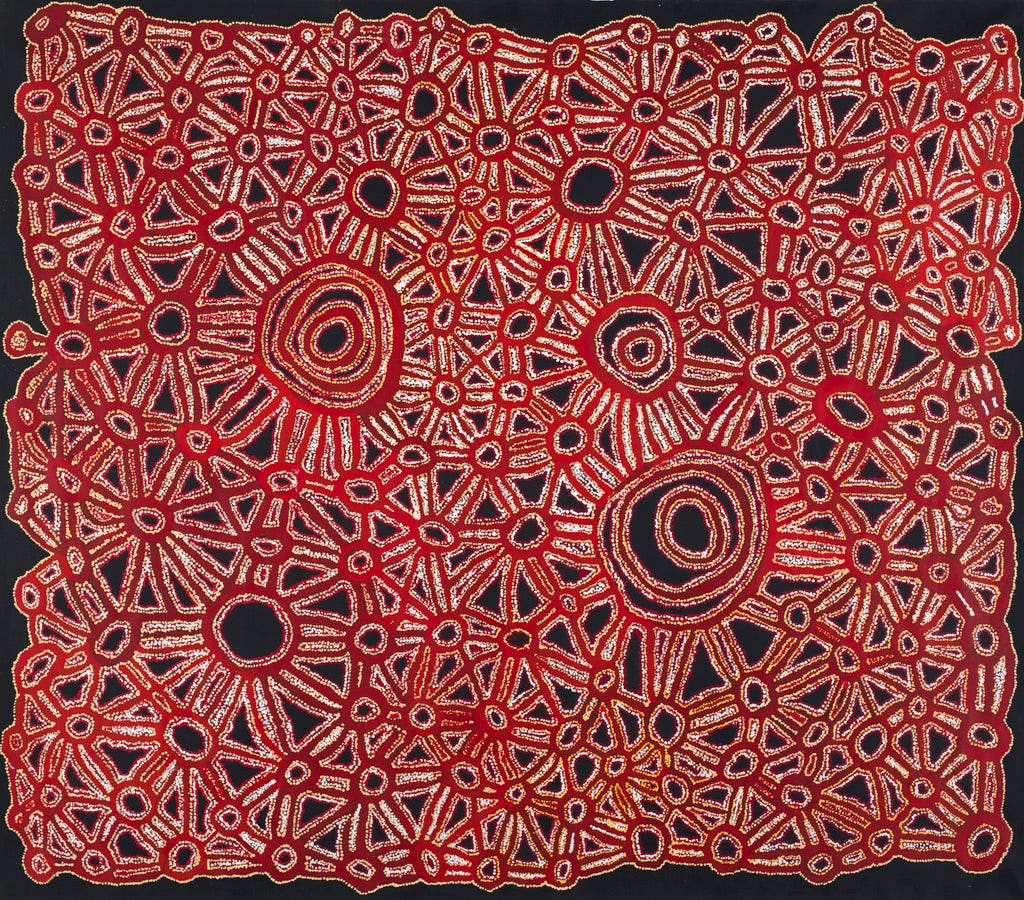

Another difference is that the artists in this exhibition are, obviously, painters, and not musicians in the narrow western sense. But in fact, more than ‘just’ painters, they are artists, singers and dancers of the tjukurpa, practitioners for whom the performance of ritual song and dance is the same as the performance that is the making of the painting (on rock, body or ground as much as on canvas) of that song or dance.1

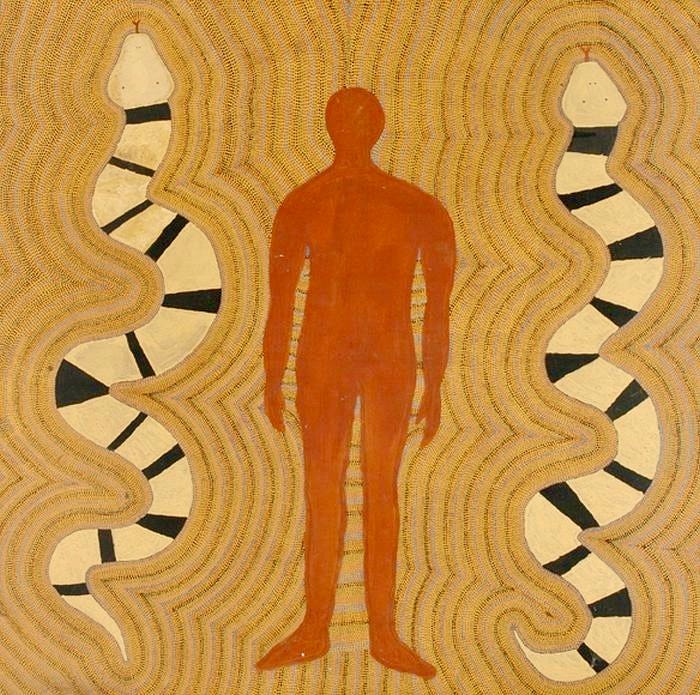

Not only are these apparently different expressive modes - painting, dance and song - so closely related in Aboriginal culture as to be interchangeable, they are at root all statements of the same thing: the truth that the artist’s very identity (and not just as an artist) is one with the continuum of all existence – above, on and below the sentient earth.

The idea that the artist/performer might be separate either literally or theoretically from their artwork is a western misunderstanding of Aboriginal culture’s embrace of all creation through all time: past, present and future, the ever-present and always-active everywhen as W.E.H. Stanner memorably called it.2

With this insight we can see that each work is in fact a self-portrait, through which the performer, primarily an artist in this case but also a singer and dancer, identifies her- or him-self with what westerners call Creation. The making of each painting reiterates the truth that Creation is not a past event. Each and every canvas here is a physical manifestation of that truth: each one literally holds that truth within it.

A corollary of this is that it is the actual place or event that is its subject, no different from the Country on which the dance might have taken place, or the skin of the people to whose bodies the designs might have been applied. Touch it and you touch that place, that connection and that timeless continuum.

But whatever our understanding of the metaphysics from which these paintings spring, one thing is clear: the works displayed here all resonate as art. They emanate, give out, and poetically express, enormous power, dignity, grandeur and authority. Standing in front of them, or even just entering the room, we have a sense that they are quietly rearranging our brain and body molecules. Once experienced, they become like sleeper cells, embedded in our consciousness, powerfully advocating for a wider and deeper sense of the universe of thought - or multiverse, rather - in which we can operate.

How, you might ask? An impossible question, but any attempt at an answer would probably need to point out that all these artists are, or were before passing way, senior cultural practitioners steeped in the lore and law of their life-world. They are and were remarkable Australians, and they have given their truths generously for their fellow Australians to share here. So many have passed away now and with the changing of their life-world we perhaps won’t see their like again. But their paintings continue to vibrate with a phenomenal life force. Never merely abstract art (despite surface appearances3), they are self-portraits of artists at the peak of their powers. They are elemental, irreducible statements of the continuum of all existence – past, present and future in one mystic expression.

Dictionaries will tell you that ‘transcendence’ means going beyond or above the range of normal human experience. Our hope as curators of this exhibition is that a more reconciled future awaits all Australians who accept the generous invitation of these artists to make that journey of discovery.4

All artwork copyright resides with the respective artists.

All paintings courtesy the Sims Dickson Collection and Archive.

Our culture and art is not separate, it is all one. We are artists, dancers and singers of the Tjukurpa, (Inawintji Williamson, artist and co-founder of Ananguku Arts, peak body for Anangu artists of the APY Lands - quoted in Alpiri Wangkanyi, published by Ananguku Arts, autumn 2010 edition).

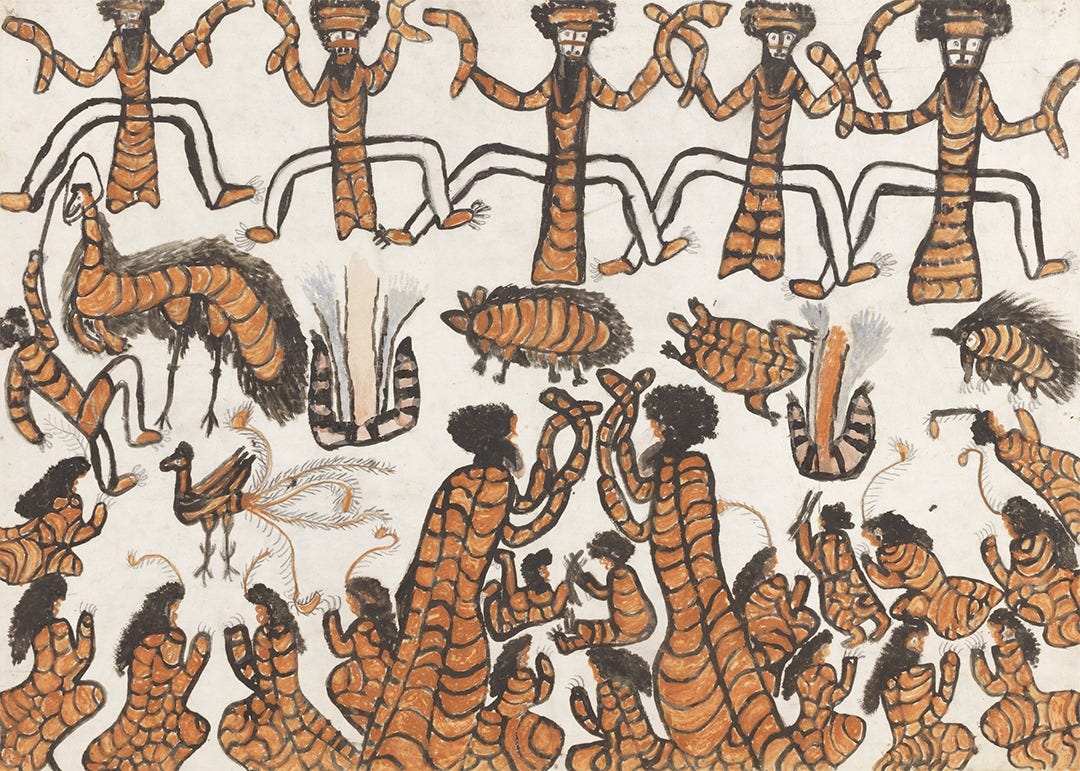

Extrapolating further, we can say that if the act of painting a tjukurpa/dreaming story is performatively the same as dancing or singing it, then the modern Aboriginal painting movement born at Papunya in 1971 has been an incredibly powerful act of resistance, in direct line of descent from the 19th century drawings of ceremonies, by William Barak (1824-1903, Wurundjeri), Tommy McRae (c1835-1901, Kwatkwat) and Mickey of Ulladulla (c1820-1891, Dhurga) most famously, among others.

A lot of what you paint is in your heart and mind rather than what you see, (Iwana Ken, artist and ngangkari, a traditional healer - quoted in Painting the Song, by Diana James, p.160).

Our paintings are our hand in friendship to you. Tjukurpa – true stories, (Eunice Yunurupa Porter, artist and Warakurna Artists Chairperson, speaking at Desert Mob Symposium 2009).