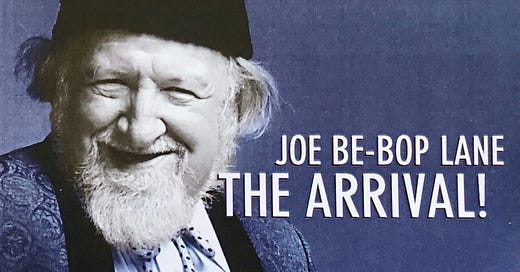

JOE BEBOP LANE - wayward genius of the jazz outerworld

If jazz is the sound of surprise, then Joe Bebop Lane was the very definition of the art form.

“Music is about getting away from your doubts, imposed by other peoples’ discontent”.

A world away from its American epicentre, an idiosyncratic Sydney variation of bebop and post bop organically bloomed, a nuanced local expression obviously influenced by, but not in thrall to, its originators. As with punk, rock, pop, opera even, when fearless Australian artists (and Joe most certainly was fearless) put their mind to something, you never quite get what you expect. Joe Lane, vocalist extraordinaire, typified that confident Australian attitude, to take on and bend.

He was a wayward genius of the jazz outerworld who spoke the language of bop with a vocabulary all his own.

An encyclopaedia of the great American songbook, the bedrock of his art, he attacked each performance with a verve born of his deep love and respect for the genre. He once told me his favourite singer was Ella Fitzgerald, but Joe was no copyist. He had a febrile ability to get to the heart of a song, and from it pull out amazingly original sounds. Hers was the art of the possible. His the art of the impossible.

Joe worked with the best musicians and trusted them implicitly to hold him up as he took off, and they responded with loyalty and insistently swinging performances, never less than exciting, often quite moving. Mostly it produced remarkable results. Improvised notes, sounds, words, muscle movement, all flowed. He was emboldened by supreme confidence (sometimes overconfidence, and the high wire didn’t hold) to take even the tritest of lyrics far outside, mined for every ounce of poetry and potential, turning listening into an adventure safari on which you were never quite sure where you’d end up.

Joe was never embraced by the mainstream, and performed mostly in small pubs and bars, no stage, the crowd milling, boisterous, along for the ride, rules of musical decorum about to be broken, ears astounded, expectations expanded. In a sense, his audience were his co-conspiritors, knowing, urging him to take flight, fuelled by shared nervous energy. It was like being a member of a secret society: Joe Lane was an underground experience, even in the bright daylight of a Sydney summer Sunday afternoon in a city pub like the Burdekin on Oxford Street or the Criterion on Park Street.

Bebop was a new, brash, high octane improvisatory expression of mid-20th century thought-action, not the same as action painting, its nearest contemporary, but equally revolutionary. The music was about freedom, but expressed as a sort of fast tempo musical Rubik’s Cube in which tunes were ritually pulled apart then reconstructed, in front of an audience, in real time. The toughest of tough gigs.

His peers were the finest local players (McGann, Pochee, Barlow…) and visiting American jazz musicians like Rahsaan Roland Kirk, who in 1974 declared Joe the best singer he’d ever heard. Words and sounds were never deployed for mere effect, always as a statement of belief, and often with a side order of theatrical drama, replete with crescendos, sudden pauses, shouts and inserted monologues. Never in a million years would you call him a song stylist, a phrase more suited to bland entertainers on daytime talk show spots, who were, ironically, backed by some of the players in Joe’s bands, nine-to-fiving for their real bread.

Whitney Balliett, jazz’s chronicler at New Yorker magazine, who titled his 1959 collection of writings The Sound of Surprise, never met Joe Lane (Baillett’s loss, not Joe’s). But if jazz is the sound of surprise, then Joe Bebop Lane was the very definition of the art form.

I interviewed Joe for the sleeve-notes to his only album, The Arrival, which I also recorded, produced and released, in 19961. His recollections tumbled forth in a remarkable stream of names, dates, places - a vital history of a transitional era in the edgy cultural outlands of a city in the throes of redefining itself.

Joe died in 2007, age 80. He was an unorthodox artist always beyond the conventional, an improvisatory genius quite literally down to the tips of his fingers that so characteristically twitched with a mimetic energy as he sang.

Ancient history. Perhaps. But culture is a continuum, and what came before is always at work in the present. Even by the early 1970s, when I first heard him, Joe had a formidable backstory, inspiring generations of musicians, injecting his personal philosophy - nothing is out of bounds - into Sydney’s uniquely receptive live scene. I’ve little doubt that Joe’s mentorship and indie attitude (he never had a manager and booked his gigs and musicians himself) was the yin to the state Conservatorium of Music’s yang, in moulding Sydney musicians like Dale Barlow and The Necks to go out and take on the world, with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and as pan-genre international festival headliners respectively.

THE INTERVIEW: Joe Lane interviewed by Matt Dickson

What makes a great song?

The lyrics are important, but not that important. The melody is the most important thing about any kind of song. The way the song moves. Whether it has a beautiful harmony content. Also, whether the music swings.

Bebop is your middle name…

It’s inherent, and inheritance. I was born swinging. I had it when I was a kid, when I was 12, 13, I used to scat then. Even when I was at school, we used to go to the School of Arts Hall in Canterbury every Sunday night. Billy Walker, Mark Bowden, Duke Farrell and me, in 1940, so I would have been like 13…. I used to go round the theatres, round about 1941, where they had a band during interval, and they’d have these amateur programs, singers, jugglers, all kinds of acts, and it would be audience applause that would tell if you were the winner. I would go on and sing Sinatra songs and things like that. I was already conscious of people like Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong, I was aware of them in the ‘30s, cos I used to go round to my cousin’s place and play his records. They’d go out dancing to the Trocadero and leave me with the record player and their records, one of those old wind-up machines. So I’d be listening to Harry Roy and his Tiger Ragamuffins on Regal Zonophone, then I started buying Tommy Dorsey records and listening to Sinatra. Then Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton and Chicagoans like Bix Beiderbecke, and Duke Ellington who was a big influence on me, and in 1944 I saw Artie Shaw at the Trocadero. I would have been about 17 when I first heard Charlie Parker, 1944, in the 2KY Auditorium. Wally Norman brought these records back from America.

Where did you first start singing bebop?

It was virtually unheard of, well, that idea goes back to when we all used to go to the Park View nightclub, way back in 1949-50, the very early times of bebop. I spent about four years with Roy Maling, the guy who most influenced modern progressive jazz in this town. He’d presented his own ballet in Germany before the war, the first Australian to write a ballet. He was a piano player, played like a cross between Teddy Wilson and Lennie Tristano, but it wasn’t until he met us that he got into Tristano, cos in the early days he was listening to Art Tatum. Roy was the orchestra conductor at the Regent Theatre in George Street when we used to go to him for lessons. He used to have a studio, and when he finished his classes, we used to go down there and jam til morning, down in Bond Street near George Street. That’s where bebop first began, in Roy Maling’s studio. I met Roy in ’48 after I got out the army. I was already scatting and listening to Bird then, but once we started working with Roy he started telling us what the music was about. It all built up into a form of freedom that I found within the music. The longer I did it the freer I became….

… After the war there were still thousands of black American soldiers here, they didn’t go home until 1947, the whites probably all went home first, and they all used to go out to the Parisian Coffee Lounge in Campsie, where Duke Farrell and Ronnie Gowans used to play. It was just a fantastic time. In 1948 we started the New South Wales Jive Club at the Newtown School of Arts Hall. Lee Neilson used to dance there, so did Norman Erskine. Then we were all going to places like the Park View, a nightclub built into the side of the cliffs overlooking Cooper Park. We used to jam there and play bebop, round about 1950. And out along Anzac Parade there was the Kelso Club where Merv Acheson and all the old crew like Ronnie Mannix and the guys out of the Cec Williams and the Trocadero bands – Jerry Sayers, Frank Coghlan, Dave Rutledge – would all go. When the depression hit in 1950 all those clubs closed. Nobody had any money. Sammy Lee’s club up in York Street closed, all those clubs. We had to go looking elsewhere, so I went to Cooma, me and a trumpet player named Billy Rayner and one or two others, and a couple of dancing girls, went up to play the Snowys. I was singing there, and we borrowed the Mayor of Cooma’s bass and the piano player taught me the notes, and that’s how I started to play the bass. We used to broadcast on a Saturday night to Sydney from Cooma…..

We had the first band in the El Rocco, and that was early, about 1952. It was called the El Rocco Restaurant then, and Arthur James’s father ran it. We got the gig, Roy Maling and me, Jack Kraber on bass, Wally Ledwidge on guitar. We used to play there on weekends. We weren’t playing avant-garde bebop, just standards, because it was just a gig…

You’ve worked with some players virtually right throughout your career…

Yeah, that’s right, because they all grew up with the music. Since its earliest inception. We can’t forget guys like Charlie Munro, he was the first bebop saxophone player in Australia I ever heard. That was when I was in the army in 1946. I remember going to Kings Cross on leave, going to the Roosevelt Club in the Cross and hearing Charlie Munro’s band playing bebop. This was about the time Wally Norman went to America and brought back the first bebop we’d ever heard. He brought back the Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker records. It was like a coming, an event, and we all participated. Charlie’s only been gone a couple of years now, he was such an important voice, in the mainstream of bebop and beyond.

Even some of your current band have been with you for over 30 years…

There’d been a do at the Musicians Club, and afterwards I said to some of the guys, there are some young guys playing out at the Mocambo at Newtown, why don’t you come out there with me, so we went out to Newtown. This would have been in ’57. And we encountered guys like Sid Edwards on vibes, Dave Levy on piano, John Pochee on drums, and Bernie McGann. The young Bernie, playing the alto saxophone. I thought he was bloody astounding then, when I first heard him. So I used to go there pretty regularly on a Sunday night. And that’s where a lot of young people became aware of bebop, because I just went along and sang bebop with these young kids. I think I was a big influence on them. Even in the early ‘80s I had Levy with me at the Criterion. Young Roger Frampton, all those young guys, Steve Russell, so many, Peter Boothman, James Morrison, Dave Colton, Paul Andrews on a Thursday night, then we all emigrated upstairs, so we were doing downstairs on a Thursday and upstairs on Sundays at the Criterion.

We didn’t last long at the El Rocco the first time, but a little later Arthur the son took it over and started running it as a coffee lounge. Levy and Pochee and Winston Stirling got a gig there on Friday night, about 1956 or ’57. I used to work there with Bobby Gebert on piano, John Sangster on drums and Ron Carson on bass, then with Serge Ermoll on piano with Bruce Johnson on saxophone, then when Bruce went to England I got the gig with Serge, Lenny Young on drums and Neville Whitehead on bass. Then about ’57 I formed the Dee Jays, and had a blue with Johnny O’Keefe because he took my band. They rang up and said they wanted to work with O’Keefe because he paid them to rehearse. You go with Johnny I said, I’ve got the gig at Joe Taylor’s Corinthian Room and you guys can get stuffed!

Did you have any formal training?

I’ve never been truly interested in sounding like anyone in particular. To a certain extent I’m creative in my own way. I like to think of myself as being somewhat of an individual, without being ridiculous and saying I’m totally original, because no-one sings a song like me. When I sing a song it’s just a total and personal involvement in the song.

Is there a political message in bebop?

The political message is self-expression, your attitude, and the way you adapt what you have learnt. It’s all to do with not listening to other people too much, and how you create your own ideology, your own message. You have to find your own individuality and maintain it. And you’ve gotta take chances. Music is about getting away from your doubts, imposed by other peoples’ discontent.

1990s gig flyers design © Matt Dickson, all artwork and images courtesy the Sims Dickson Collection and Archive.

Now out of print and still the only recorded Joe Lane material ever released. Some tracks, like Well You Needn’t linked above, have been uploaded to YouTube by Paul Andrews, a regular tenor saxophonist in Joe’s line-ups, as well as some live performances like Body and Soul, also linked above.