DAVE SANDS: how one photograph can talk to us about Australia's past, present and future

Champion boxer Dave Sands died 71 years ago this week, aged just 26. This magnificent image is a tipping point in the photographic depiction of Indigenous Australians.

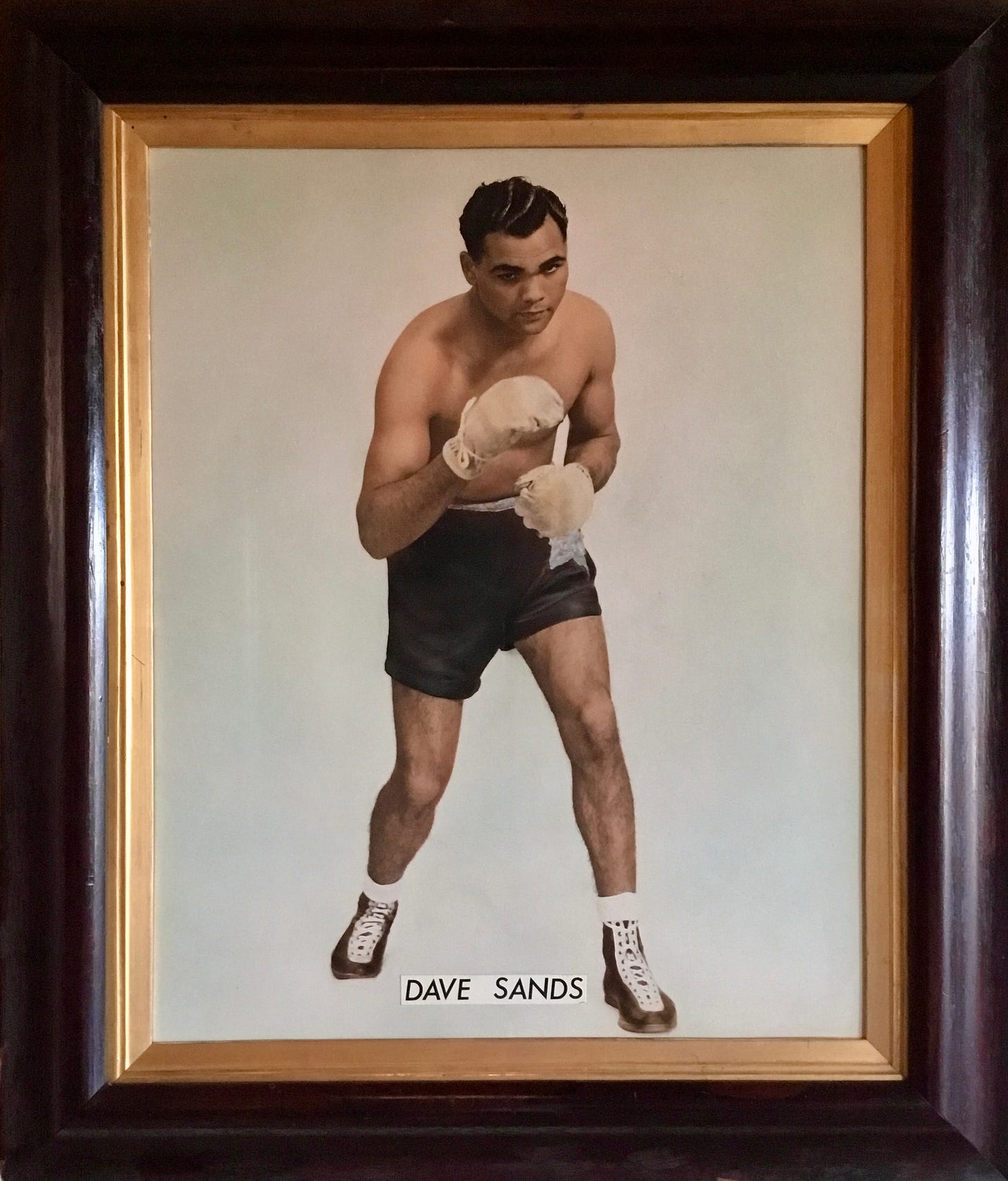

Dave Sands, hand coloured gelatin silver photograph, photographer unknown, circa 1950. Dimensions 49 x 39 cm (image), 66 x 56 cm (frame). The same image as the well-known black-and white postcard-size version, issued as fan merchadise. But this is the largest known version of the image, and the only known coloured version. Hand coloured from the original negative, in original oak frame.

DAVE SANDS

Aboriginal Australian boxer Dave Sands (1926-1952) is recognised internationally as one of the greatest boxers never to have won a world title. He was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1998.

A Dunghutti man, Sands was born David Ritchie in 1926, on Burnt Bridge Mission near Kempsey on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales. He moved down to Newcastle in 1941 to train with Tom Maguire in Beaumont St, Hamilton, joining his brother Percy (all five of Dave’s brothers were boxers). The two brothers lived at Maguire’s gym and Maguire would act as Sands’ manager for most of his tragically short career. Around this time, all six Ritchie brothers adopted the surname Sands in honour of the train guard who enabled Percy to travel to a fight without having to pay the fare.

The Fighting Sands Brothers, photographer unknown, circa mid 1940s. Left to right: Clem, Percy (aka Ritchie), George, Dave and Alfie Sands (Russell not pictured), in the green and white livery of the Star Gymnasium, Hamilton, Newcastle, (National Portrait Gallery Collection).

In 1946 Dave Sands won both the Australian middleweight and light-heavyweight titles; in 1949, in London, he won the British Empire middleweight title; and in 1950 he won the Australian heavyweight title. The following year he narrowly missed the opportunity to fight Sugar Ray Robinson for the World middleweight title. Acknowledged as the number one contender, many experts believe Sands would have beaten the legendary American champion – rated the greatest boxer of all time - had Robinson been willing to fight him; reluctant to risk his crown, he reportedly said, “I’d need a lot of money to fight that man”.

Sands won two fights in the United States late in 1951, but soon after his return to Australia in 1952 he was killed when the truck he was driving to a timber cutting job overturned at Dungog. He’s buried in Sandgate Cemetery, Newcastle.

Sands fought 110 professional fights, for 97 wins – 52 by knockout, a phenomenal record. Despite career earnings that stood at around £30,000 at the time of his death, he died a pauper, his fortune having been dissipated by manager’s fees, taxes, and his own generosity.

In the often-opaque world of international boxing promotion, Sands never got the chance to fight for a World crown. But he beat American fighter Bobo Olson twice, in 1950 and again in 1951 (the first ever bout to be televised coast-to-coast in America), before Olson himself succeeded Sugar Ray Robinson to the World middleweight title in 1952, after Sands’ death. In a moving tribute, newly crowned World champion Olson declared, “If Dave Sands was still alive, this title would be his”. A poignant epitaph for one of the world’s greatest fighters.

THE PHOTOGRAPH

The way in which photographic portraits of Indigenous boxers such as the Sands brothers, Elley Bennett and Jack Hassen were presented to the Australian public in the late 1940s and early 1950s - on boxing magazine covers, as publicity photos or fan merchandise in postcard format, and as large framed prints adorning the walls of gymnasiums and pubs - represents a turning point in the history of portraiture of Indigenous Australians. Perhaps for the first time, Indigenous people are not portrayed as anthropological curiosities, specimens of “the last of their tribe”, or targets of social derision. These men are presented purely and simply as elite athletes and sporting heroes, without explicit or tacit reference to their skin colour or ethnicity.

It took a little over one hundred years from the birth of photography in Australia, but in this beautifully hand-coloured large-scale portrait of the great Dave Sands in fighting stance, taken at the height of his career, we encounter an image of an Aboriginal man that is both powerful and humanising, emphasising the subject’s prowess in a universal, and not merely parochial, context. At the same time, the image is still one with which any Indigenous Australian would identify with immense pride.

THE LEGACY

But there are other dimensions to this image.

In the context of portraiture more generally, it reminds us that fame is a fleeting and transient thing, even for champions. In his lifetime Sands drew crowds in the tens of thousands to his bouts. Fans queued around the block just to watch him train. A generation after his death the name Dave Sands has been added to this portrait using Letraset to identify him, likely in the 1970s when the Letraset system was a popular and cheap way to create lettering.

More particularly, as we know from our own contemporary experience, respect for Indigenous sporting heroes is a fickle and fragile thing, taken away by Australians as easily as it is given. The shocking abuse heaped on champion Indigenous AFL players Adam Goodes and Nicky Winmar is testament to this.

And there is no little irony in the probability that in Sands’ own day the very same pub that might have hung this image would have refused Sands a drink, due to legal restrictions on the service of alcohol to Aboriginal Australians, in force for almost another two decades after this photograph was taken.

Let’s remember too that this image dates from a time fifteen years before the Freedom Rides shone a light on entrenched racism in Australia, and nearly twenty years before the 1967 referendum. In fact, it reminds us that Sands lived his whole life under race-based institutionalised control, from his birth and upbringing on Burnt Bridge Mission until his early death.

Nonetheless, in a broader and more positive view, two decades before Evonne Goolagong and fully five decades before Cathy Freeman, this is arguably the first photograph to put an Aboriginal Australian in an international rather than a parochial context.

SOME PERSONAL REFLECTIONS

In the 1940s and early 1950s two Aboriginal Australians were household names: Albert Namatjira and Dave Sands.

Why has posterity not accorded Dave Sands the status Namatjira’s legacy enjoys - what his exploits by any measure undoubtedly deserved.

Perhaps it’s because Namatjira was embraced by the culturati and the aspirational middle class. Sands, on the other hand, was idolised by the working class.

Namatjira's paintings of his Arrernte country were exhibited at high-end fine art galleries and bought by state and national institutions and wealthy collectors. He was even introduced to the Queen by a condescending white Australia. Then when his images were exploited on calendars, prints and biscuit tins his name became known by a wider middle class. His is, to this day, the best-known Aboriginal Australian name.

The trajectory of Sands’ fame has been different - still revered in boxing circles but unknown by the wider public - but no less valid for re-examination for all that.

His art was the art of the pugilist. His rise to be a champion boxer was avidly cheered by hundreds of thousands of ordinary Australians, battlers who were not the same Australians as those who owned Namatjira’s paintings, but their numbers were huge and their regard for their hero ran along similar lines. They related to his natural ability, his dedication to his art, his underdog status as an Aboriginal in a white world, his overseas victories against top-rated international opponents.

Indeed, for much of his career Dave Sands, Dunghutti man, was as widely celebrated an example of Australian sporting prowess as the legendary white cricketer Don Bradman.

Dave Sands’ funeral cortege, Newcastle, 1952 (Newcastle Herald Collection).

It’s important that Dave Sands’ story be better known. As activist Gary Foley has written in his history of the Aboriginal protest movement, the 1950s were key to the historic shift in attitudes that led eventually to the overwhelming victory of the Yes vote in 1967. Support for the subsequent land rights movement and demands for equality, justice, and restitution of Aboriginal control of Aboriginal destinies, can all be traced to the same pivotal period of the 1950s.

The change in public sentiment in the ‘50s is vividly illustrated by the big turnout – almost entirely of white Australians - at Sydney Town Hall in 1957 for the launch of the Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship, established by activists Pearl Gibbs and Faith Bandler, a key moment in the history of Aboriginal rights.

Why the change in white Australia’s attitude in the 1950s, even while Assimilation was at its peak? It seems reasonable to suggest that the widespread acceptance, respect, popularity and celebrity of the two best known Aboriginal Australians, Albert Namatjira and Dave Sands, was a key factor in swaying white Australians’ sentiment.1

Others, black and white, had been working hard before them, but it was these two Aboriginal men who opened the door for change, and the ripple effect of that is still being felt today.

Can a single photograph speak more eloquently than this one does on such a momentous matter as the place of Aboriginal Australians in the national psyche?

So much more than just a supremely beautiful artefact from the past, still today it weaves ongoing political, sporting, social and historical threads into its powerful presence. It’s a portrait alive with contemporary resonance.

All text and all images copyright © Sims Dickson Collection and Archive except where noted.

Not to discount other contributions, including the 1955 film Jedda, a flawed (it was re-titled Jedda the Uncivilised in the UK) though largely sympathetic treatment of Aboriginal issues starring young Anmatyerre woman Rosalie Kunoth and Tiwi Islands man Robert Tudawali as leads; and Yorta Yorta singer and songwriter Jimmy Little, who appeared on television and had chart hits from the late 1950s. But Namatjira and Sands both pre-dated these and were hugely well known and admired.