RECENT READING 2: You've got to fire up

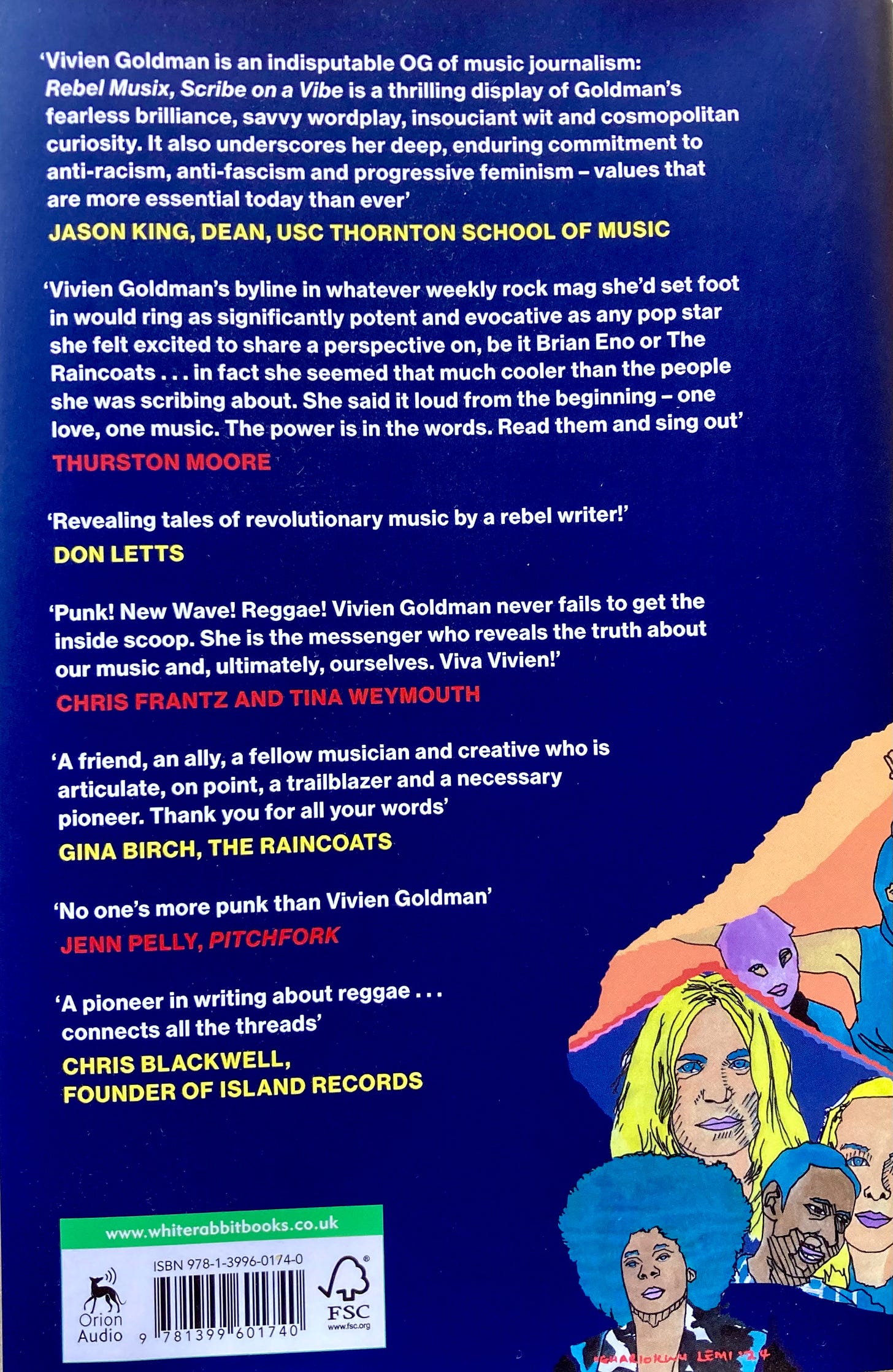

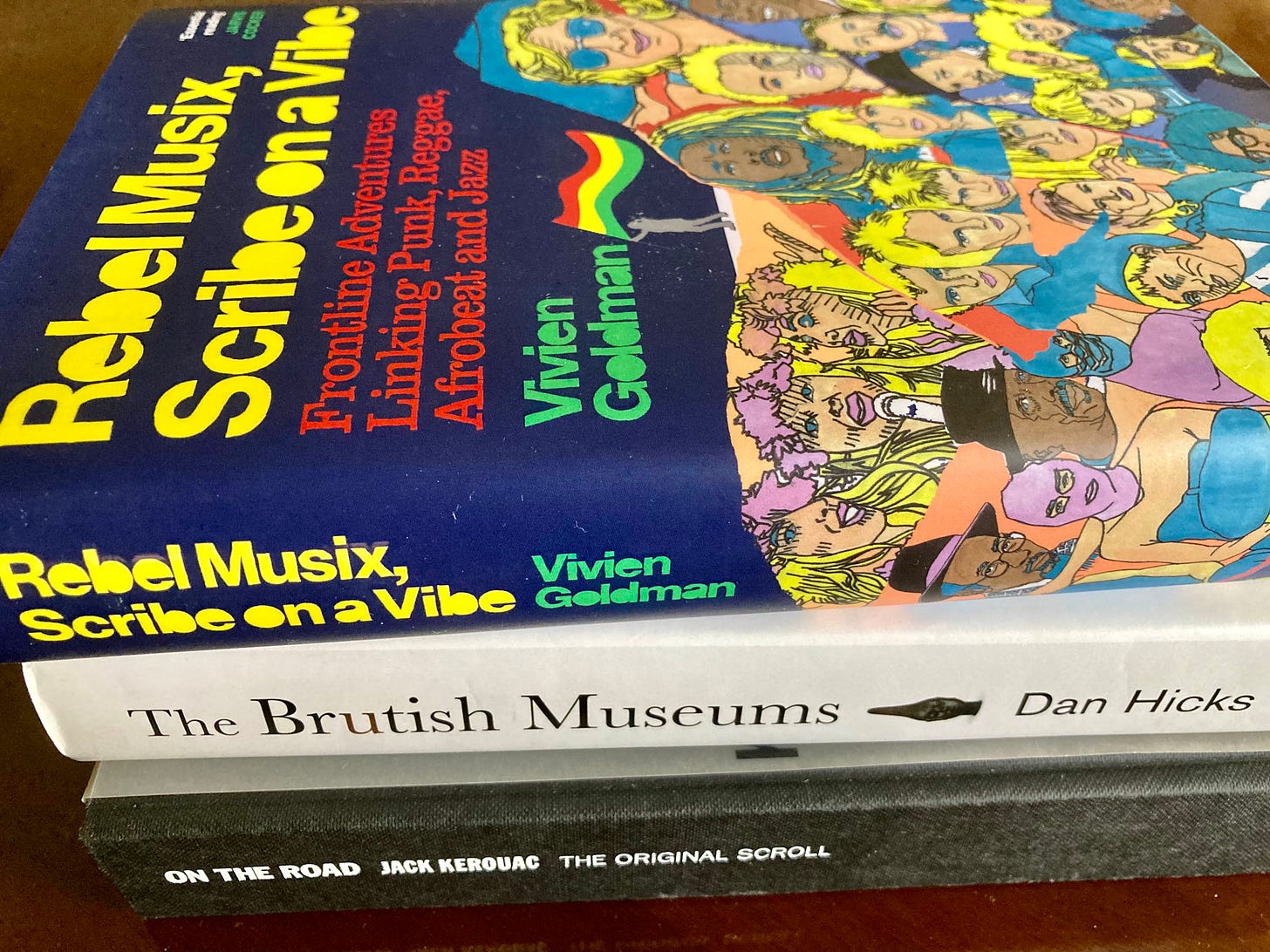

Vivien Goldman's "Rebel Musix, Scribe on a Vibe: Frontline Adventures Linking Punk, Reggae, Afrobeat and Jazz"

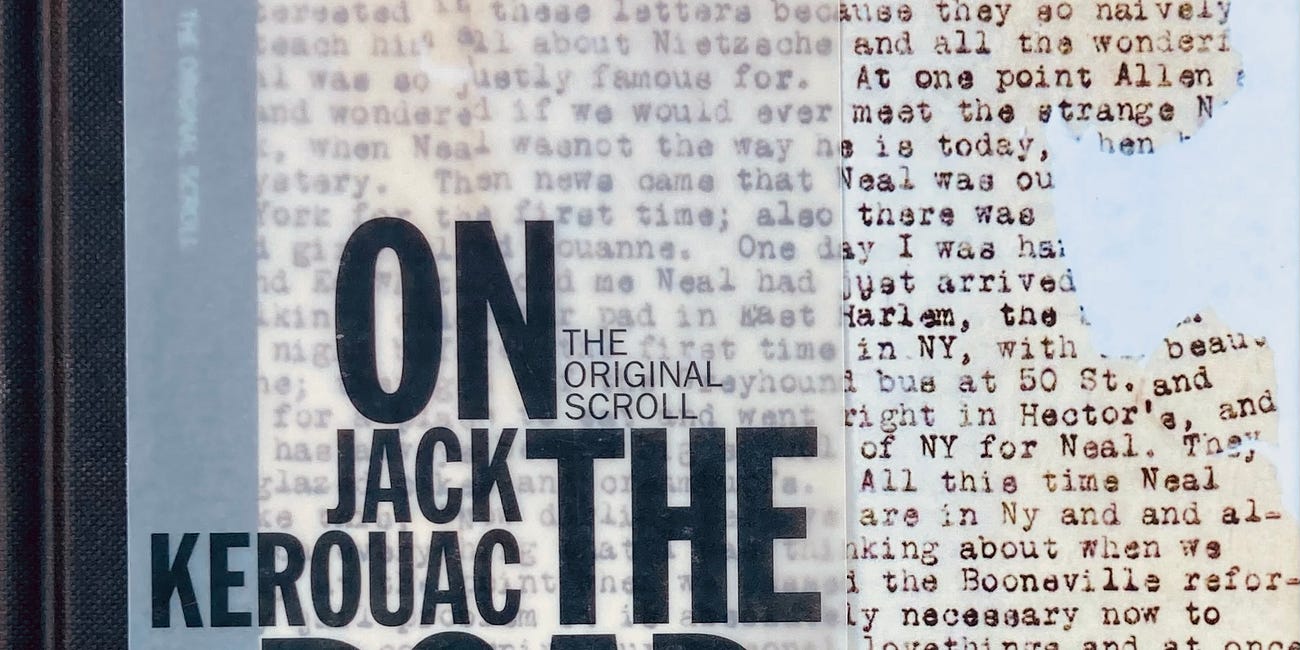

Rebel Musix is about music, but it’s also about creativity, imagination, history and change. Thinking differently and acting on it. As Jack Kerouac wrote in Desolation Angels, “The only truth is music”. By which I think he meant music has the power to connect us directly to some higher mental and spiritual state. Which is why the musicians Vivien Goldman has chosen to interview over the past half century and gather here, all of them advanced thinkers-and-doers throughout pioneering careers, make such crucial reading for anyone seeking insight into the elevating sweep of 20th and 21st century creative popular music.

Vivien Goldman was foremost of the groundbreaking British women journalists proselytising punk and reggae in the UK music press in the second half of the 1970s (Caroline Coon and Julie Burchill were two others from that fecund time). She’s still writing, and Rebel Musix anthologises a selection from across a signal career.

She’s first generation British, daughter of refugees from Hitler’s Germany, born in 1952 into a white world of Empire and fading glory. That weltanschauung got a right royal dose of culture-shock in the 1950s and '60s when thousands of immigrants arrived from the rapidly disappearing pink parts of the globe, and pissed-off newly enfranchised youth demanded its own music. By the mid '70s the seeds of what she calls Rebel Musix and Bob Marley called the Punky Reggae Party (the flip side of his Jamming single) were blooming into an incredibly diverse musical era that blended black music - from the Caribbean, Africa and the USA alongside home-grown - with punk. It was a catalysing moment for two-fingered calling out of oppression and orthodoxy, Oh Bondage Up Yours and Mash Down Babylon style.

Between 1979 and 1982 Goldman also made the kind of music she loves writing about, helped by John Lydon and Keith Levene from Public Image Ltd and the cream of UK reggae players and dub experimenters (which tells you something of the esteem in which she was held even in her earliest years of writing). Those tracks are now compiled on an album called Resolutionary. Her single Laundrette was an empowered critique of typical male attitudes of the time, and she subsequently enhanced her feminist credentials with Revenge of the She-Punks, a history of punk’s women artists.

Maybe because she too feels like an outsider among marginalised newcomers and punk refuseniks, Goldman seems to have always been drawn to write about the square pegs around her. Especially good are fearlessly revealing accounts of Rasta men Bob Marley and Peter Tosh: wonderful musicians who Goldman had worked for as publicist at Island Records before the Wailers made it big beyond Jamaica. It’s Marley’s body-music that defines the positivity (aka the vibe) of the times, dark though they were in many ways (skinheads and National Front for starters). One Love is still a sensuously beautiful song and Exodus (she was there in the studio) a still-powerful album. But my god the Old Testament Rastafarian view of women held by Marley and Tosh is offensive - and Goldman makes clear to them her objections.

If Marley’s music is this book’s heartbeat then Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti is its conscience. Visiting the USA in 1969 the Nigerian jazz saxophonist had his brain rearranged by the Black Panthers and James Brown (yep, that’ll do it, every time). Back home from the US he ditched the Anglo half of his surname (Ransome) and became Fela Anikulapo Kuti (he who carries death in his pouch), pan-African cultural and political activist. Songs began to valiantly catalogue the corruption and extreme violence of the military junta and its enablers the CIA and American corporations, to the insistent traditional rhythms of West Africa played by a James Brown inspired band dozens strong. Afrobeat was born kicking, fist raised. During the destruction of Fela’s compound in Lagos - a commune he called the Kalakuta Republic - by soldiers who probably danced off-duty to his hugely popular records, his mother Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti who was a pioneer of women’s rights and anti-colonial resistance was thrown from a second storey window and died from her injuries; all the women were raped, many with broken glass. He’s understandably weary in his interviews with Goldman, but resilient, that raised fist and flashing smile never far away. But Fela had unreconstructed views on women too – and 27 wives - elegantly dissed by Goldman with the nazi slogan Kinder Kuche Kirche (Children Kitchen Church) - pretty heavy coming from the daughter of Jewish refugees.

The Slits (their first press appearance), Public Image Ltd, The Clash, Richard Hell, The Raincoats, Brian Eno, Betty Davis, Talking Heads, Grace Jones, Ian Dury, Patti Smith, Robert Wyatt, Kid Creole, Curtis Mayfield, P-Funk, Public Enemy and Can also appear, in their own words and with insightful scene-setting intros by Goldman. Right there, that’s a rollcall of some of the era’s most creative acts. Later pieces cast a discerning eye on more contemporary music-making, though as she makes plain, it’s all connected, whether it be Ornette Coleman’s musing on his theory of harmolodics (about which I’m still no clearer, but Dancing in Your Head still sounds great four decades on); his pocket-cornet player Don Cherry’s work with bassist Charlie Haden in Old and New Dreams; or Neneh Cherry’s time with feminist trailblazers The Slits; or The Slits’ and Public Image’s dub excursions; Questlove playing an early James Brown track for Femi Kuti, Fela’s son; or Bob Marley’s over-arching impact on multiple generations of musical free-thinkers.

Rebel Musix is unabashedly a fan’s view inspired by a time when things were changing at lightning speed and new trends and new bands emerged every week. Goldman writes with empathy and passion, beholden to no-one: plainly she’s alive to the weight and consequence of the musical moments she’s lucky enough to be living through. One gets the inescapable impression she was born to write this stuff.

Many early pieces were dug out of a proverbial dusty box in Goldman’s attic. The tale these primary sources tell is a vital addition to the canon and the author’s serious intent to preserve them for posterity laudable (she is Professor of Punk and Reggae at NYU after all).

Most telling is that Goldman concludes her book with a 2018 piece on Mighty Sparrow, Trinidadian calypso king, and his startling 1964 recording called Slave (Bob Marley: “When I heard the Mighty Sparrow sing The Slave I knew what I wanted to do with my music”). Goldman clearly feels it too: “As Sparrow soars into the line, Oh Lord, I wanna be free! the track stops so abruptly that it feels as if the listener is leaping from a cliff into the ocean to escape the slave-catcher’s dogs at their heels”. It’s a pair with a 2024 article on Rebel Sixx, the earliest and the latest music in the book, both from the island of Trinidad.

Slave is a fusion of Afro-Cuban and calypso which I confess to not having heard before but now can tell you there are few songs with as chilling a lyric. Strange Fruit by Billie Holiday will always top that list, of course, but Slave well predates Ship Ahoy by The O’Jays (1973), an unlikely (or perhaps not) success that conjured the dark and ominous sounds of the Middle Passage (“Men women and children slaves, coming to the land of liberty” sung to the mournful sound of creaking ship’s timbers and whips cracking, in an album sleeve of African slaves chained below deck).

The world is a ghetto, sang War on the title track of the best-selling US album of that same year. It’s a good analogy for the still-rippling effects of more than 500 years of African slavery that have given rise to what Vivien Goldman has elsewhere called the Black Chord: music of incredible intensity and invention that has like a flooding river influenced music high and low including blues, jazz, gospel, soul, reggae, Afrobeat, rock’n’roll, funk, hip hop, dancehall, ska, township, R&B, even Sub-Saharan desert blues, and Afro-Latin hybrids like cumbia, rumba, bossa nova, salsa, samba and the rest. And that’s only what the global north knows about.

Mighty Sparrow’s song is forerunner to Bob Marley’s Redemption Song, and that song is emancipation set to music. Emancipation – “Emancipate yourself from mental slavery… none but ourselves can free our minds” - is what informs all the music in this book and makes it entirely contemporary – because what this music celebrates, even in its moments of greatest pain, like the slavery of Mighty Sparrow, the murder of Fela Kuti’s mother and the assassination of Rebel Sixx, is not in the Past. Rather, as Dan Hicks brilliantly shows in his book The Brutish Museums, it endures, and is very much of the Now. And the Future too.

Ornette Coleman’s son and drummer Denardo Coleman says in Rebel Musix, “You’ve got to fire up; it’s got to be urgent, even if it’s relaxed”. Ain’t that the truth. Kind of like how John Lee Hooker or Bob Marley sound. This book is like that. Grounded. But it flies.

If you enjoyed Recent Reading 2, here’s a related post to dive into…