Janet Inyika on Maralinga: "We were the survivors"

On International Women's Day let's remember an activist and artist whose accounts of her lived experience of radioactive fallout counter official histories of Australia's atomic folly.

Janet Inyika was born around the same time as the Australian government invited its British counterpart to explode atomic bombs in outback South Australia. She grew up in the shadow of those bombs, on her traditional Country and at Ernabella Mission, about 300 kms southeast of Uluru. She lived with the unthinkable: personal experience of radioactive fallout from atomic weapon testing at Emu Field and Maralinga in the 1950s.

Janet’s life bridged two worlds: the traditional culture of her Pitjantjatjara family and the hegemonic culture of white Australia. She negotiated the chasm between them with skill and nuance.

At mission-school the young Anangu[1] girls were encouraged to draw and paint, and become literate in both English and Pitjantjatjara. Janet is just one of a remarkable generation of strong women who shared that experience and became both artists and community leaders.

She was a principal mover in programs - devised and led by women - to repair, strengthen and build traditional culture in the midst of an imposed world of trauma, arrogance, violence and early death.

In particular she instigated and led the successful campaign to introduce low-aromatic Opal fuel in remote and regional Australia, which saved untold lives by radically reducing the scourge of petrol sniffing in Aboriginal communities. She was a director of the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (NPY) Women’s Council, where she worked tirelessly to end community violence against women, and promoted cultural reinvigoration through art-making as a director of Maruku Arts art centre, Tjanpi Desert Weavers, and Desart, the peak body for Central Australian art centres.

Also a traditional healer, or ngangkari, it’s true to say that she tended the open wounds of dispossession among her people.

Fast forward to 2012, and Janet Inyika, by now a senior cultural law woman, was still painting, no longer at Ernabella (or Pukatja as it is known once again) but at Maruku Arts, the Anangu-owned art centre in Mutitjulu community, at Uluru.

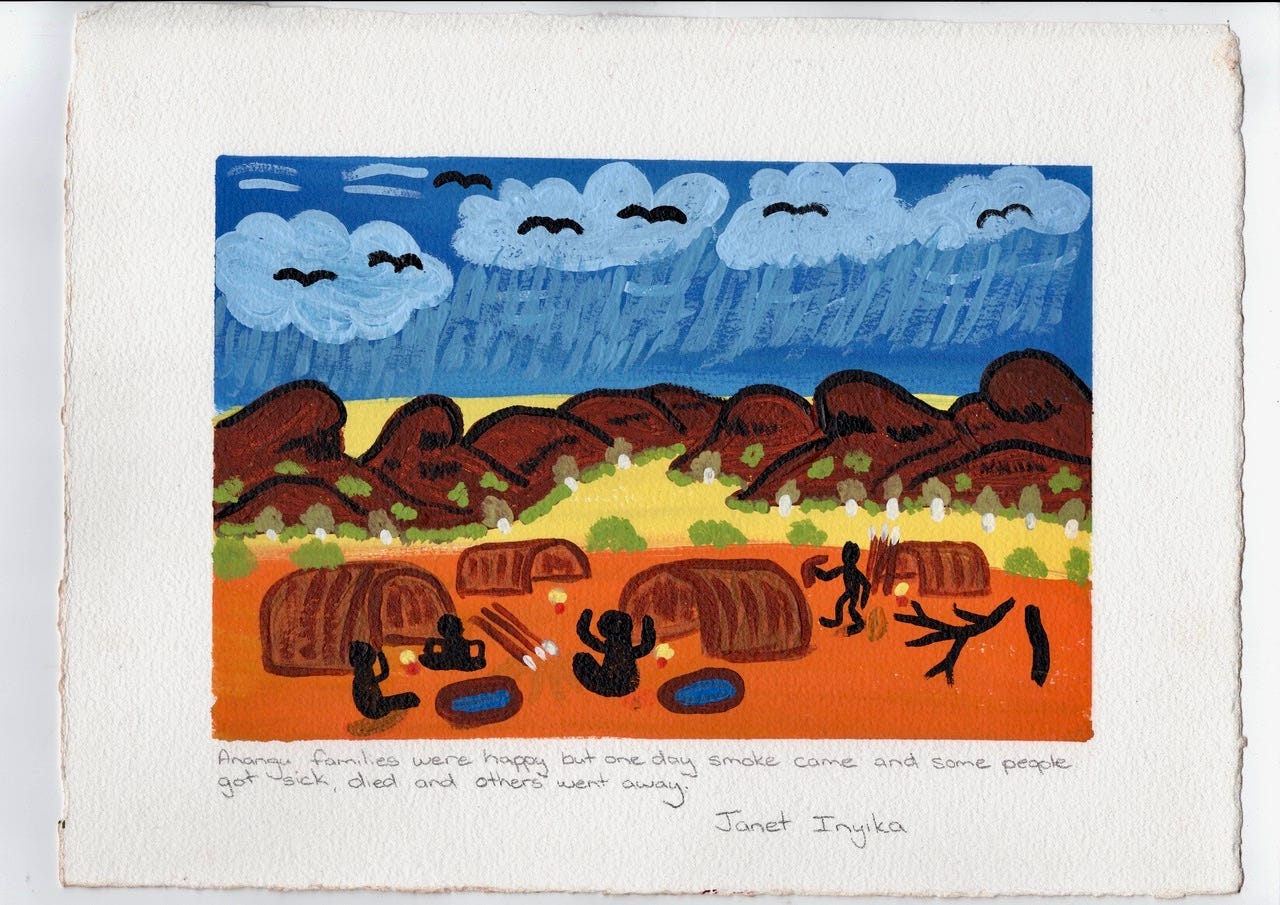

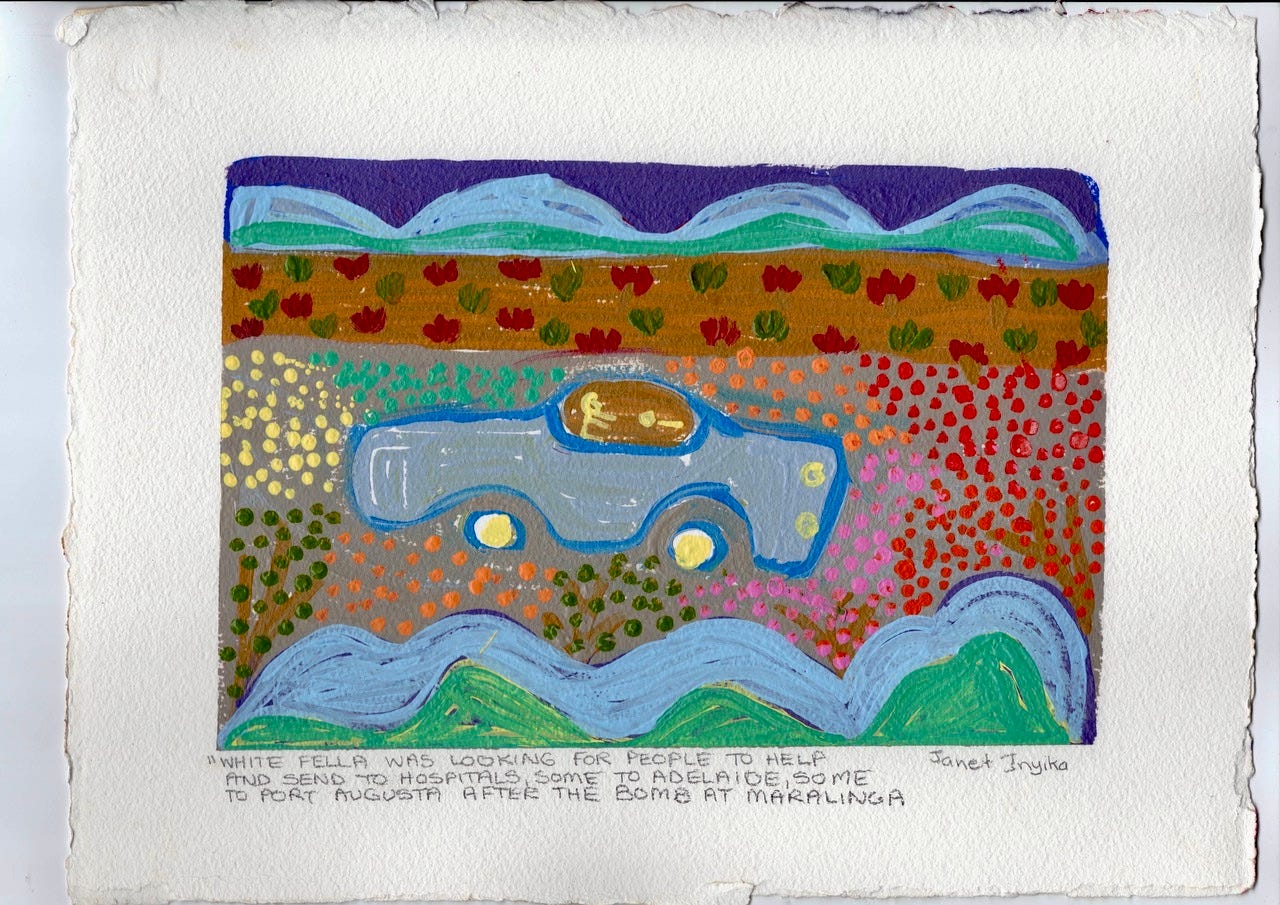

Of immense significance to our understanding of our shared past, the paintings Janet made there of her atomic bomb experience bring to light for the wider world the effects of at least one of the British atomic blasts at Emu Field and Maralinga. All the Anangu of her generation know the story.

(Anangu nearly always use the term Maralinga when referring to their bomb experience, rather than the separate place names Emu Field – where tests occurred in 1953 - and Maralinga – where tests occurred between 1956 and 1966).

Nearing death in 2016, Janet recorded the oral history of her Maralinga experience for Ara Irititja, the Anangu digital cultural archive under the aegis of the NPY Women’s Council. It was transcribed from her Pitjantjatjara language into English by archivist, translator and friend Linda Rive, because Janet wanted her story to be known as widely as possible. Not because her story is unique, but precisely because it’s not.

You can see her paintings and read her words below.

Aboriginal visual and oral histories challenge official histories and subvert the dominant document-based settler discourse. That’s not the kind of whitefella language Janet ever used, of course, but in her own inimitable way her paintings and her powerful advocacy for her people incontrovertibly do just that.

Janet’s words sing in an elegiac key, as do her paintings, but remarkably, amid loss and great sadness, at the end of her story there is hope and positivity, born of her confident belief in the strength of her culture and the ability of her Country to heal. There’s certainly no self-pity. Yet who would blame her if there were? As Linda wrote of her translation,

It is hard to quite get across just how freaked out everybody was, and how much trauma has been inherited from those days of mass deaths. Some people have never got over it, how could they? It has been questioned why there are so many cancer deaths these days, including Janet’s. I've heard it said that they didn't really escape, they only bought themselves some time. Her death by cancer was caused by Maralinga. That's what people say, and she's not the only one... "Lest we forget."

“WE WERE THE SURVIVORS”

An account by JANET INYIKA. Spoken from her hospital bed.

Also contributing is Janet’s younger brother Wally Jacob.

Alice Springs Hospital, 30 June 2016.

Recorded, transcribed and translated from Pitjantjatjara by Linda Rive. Courtesy Linda Rive and the Ara Irititja Archive. Copyright Ara Irititja.

Janet Inyika: Hello. I’m here in hospital as a patient. I am in bed. I want to tell a story about the olden days. Linda and I have talked about recording this story for a while now, so this is a good opportunity to do so. I have already painted this story, but to recap, iriti, a long time ago, many years ago now, I remember, we were camping at a place called Bob’s Well on the edge of the Musgrave Ranges. We were with a large group of Anangu, with lots of new babies and little children and toddlers. I was there with my mother and father, as a tiny little girl.

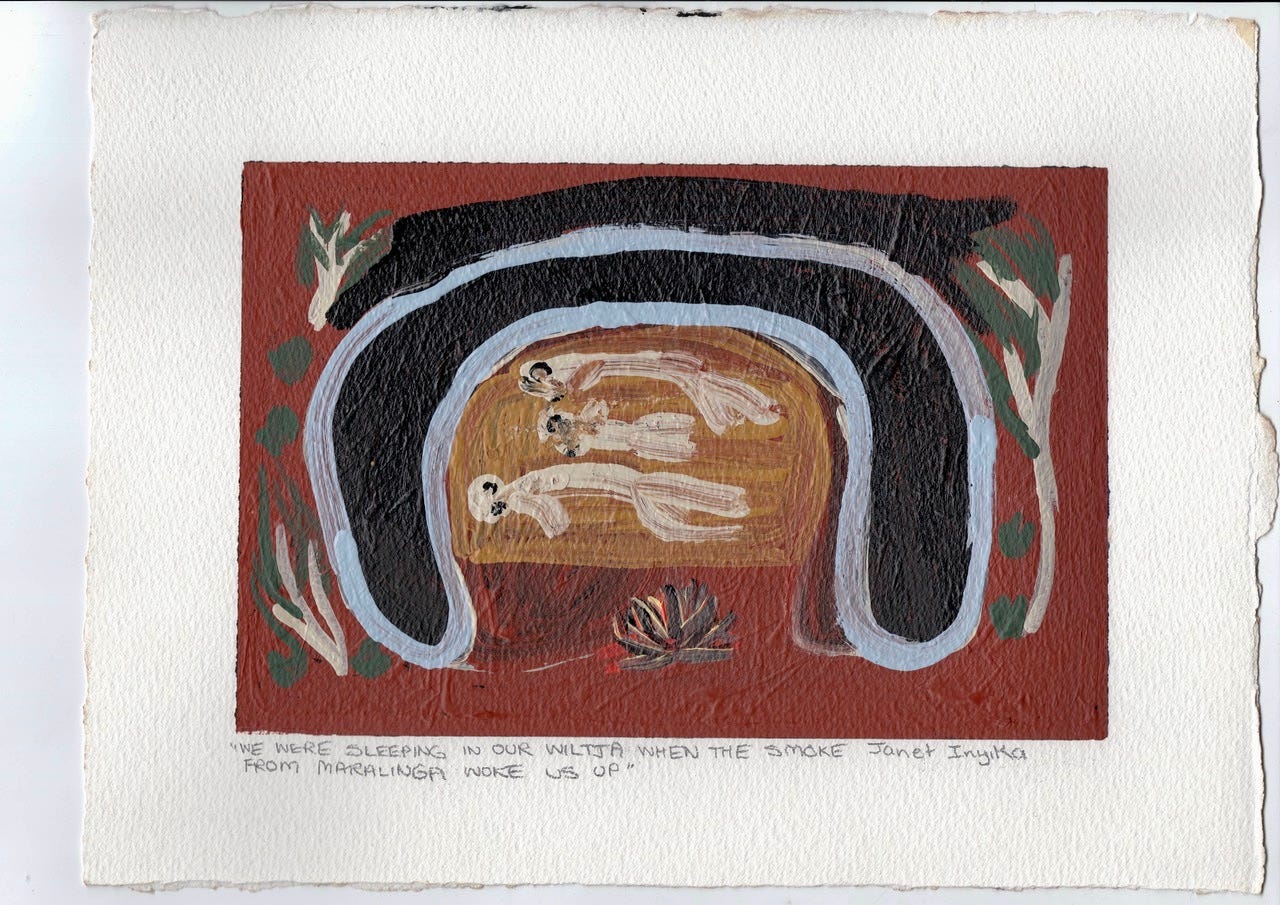

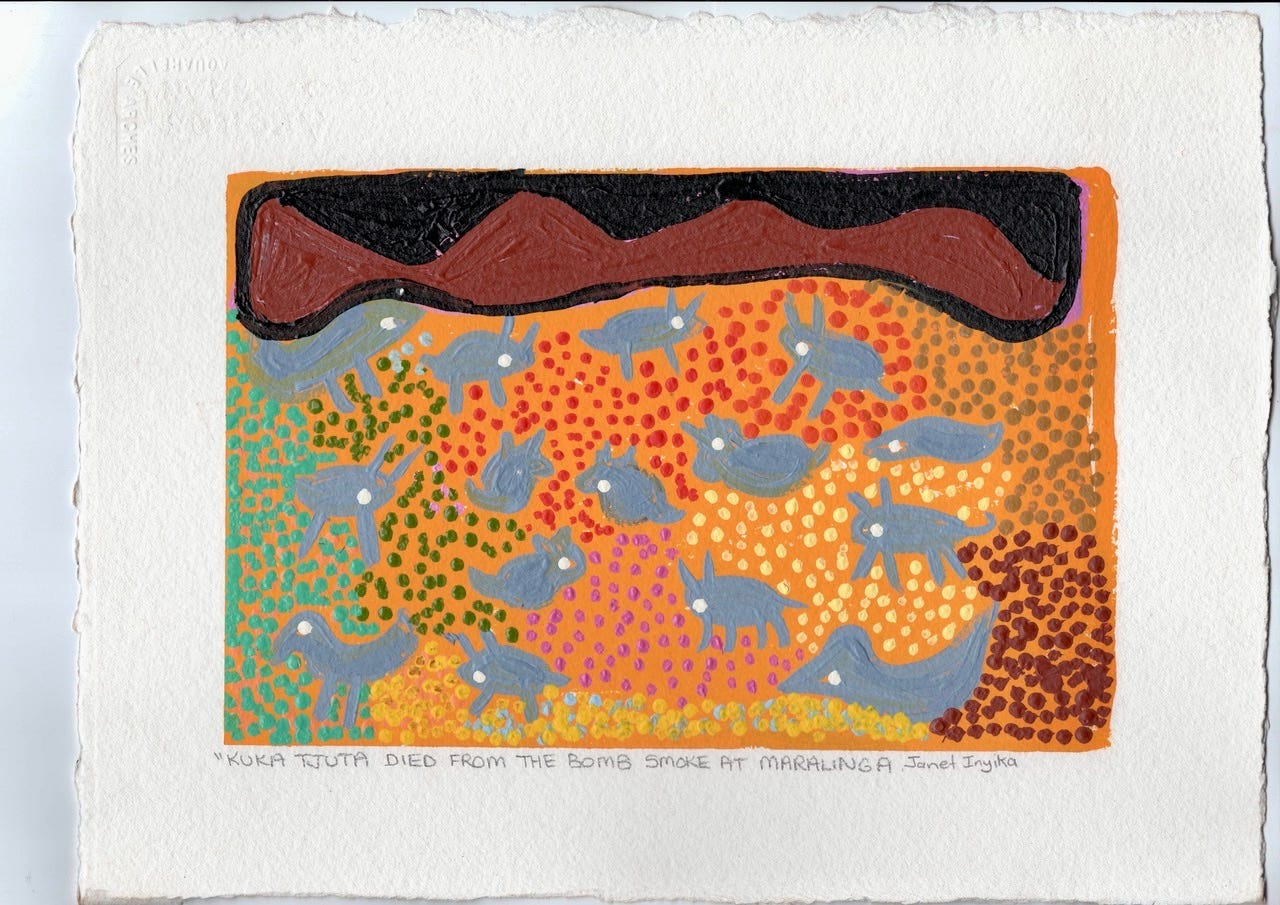

In 1953 a nuclear explosion had been detonated. A bomb had been detonated, and because of that, mum and dad had to make a dash for [the mission at] Pukatja [then called Ernabella], taking me with them….. I was one of the luckier ones. Many of those little children lost their parents during that exodus. They died en route to Ernabella, poor things. The mothers and fathers were dying and children were being orphaned. Some children died too. A bad cloud pervaded the area and the fallout chased us across the country and killed at will. Many people died in a huge area across the country. Telling this story upsets me still. I feel a deep sadness towards the beautiful relatives we lost at that time. They were simply dying in droves. I feel terrible thinking about how those parents did everything they could to protect themselves and their children but ended up dying….

The grownups were aware of the fallout, the cloud, the puyu, but they didn’t realise how deadly it was. If it didn’t kill, it made people very sick, and affected their eyes. People were going blind and losing their sight. I think everybody was affected in some way.

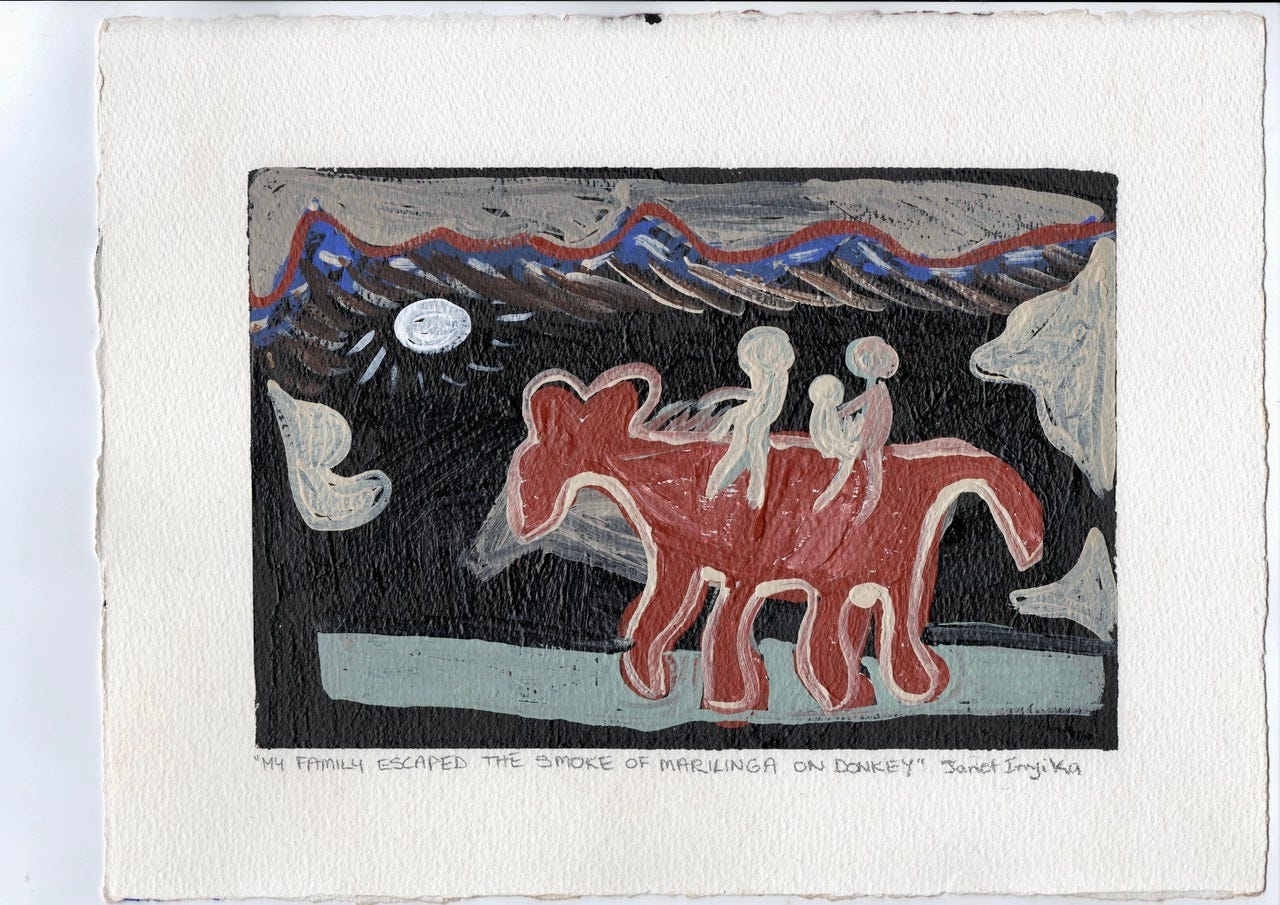

In order to escape, mum and dad put all our belongings onto our donkey and we escaped during the night, by the light of the full moon. We were on the back of the donkey. Others didn’t make it. They died before they could get away. Young children the same age as me died.

Wally Jacob: I got terribly sick myself. I nearly died. I was so sick that when we got to Ernabella I had to be sent to Adelaide for treatment…. A lot of boys my age were sick….

Janet: He was sent away from home as a little boy. He was sent to Adelaide, to a place called Warrawee. He was there with a lot of other sick children.

We had been walking around the country, hunting and gathering. We were over on the other side of Turkey Bore…. Anangu used to spend a lot of time there, going hunting and spending time in that lovely place, hunting kangaroo and enjoying a holiday [from the mission]. Other families went to Wamikata…. People stuck together in their family groups, living off the land.

I started to get sick. I wasn’t well. Dad quickly went and got the donkey, put our stuff on its back, Mum mounted, holding me, and we started cantering towards Ernabella. We were with three other families.

We left behind people, the living and the dead….

This story affects all Anangu. There are no Anangu families that were not affected. Mine is just one little story out of many. Other people walked as best they could to escape. We were lucky to have a donkey.

In one of my paintings we are riding on the back of the donkey, my father in front, mother behind, and I am the little baby squashed in between. I was being cuddled. My mum always told me this story and other people have told it too.

Wally: There were people all over the land, living on the land, married couples and larger extended family groups, people were dotted all over, spread out right across the country, and they were all affected in some way. People right up to Haasts Bluff, Areyonga, Ernabella and Warburton Ranges were affected.

Janet: Everyone was affected by that fallout. Like a bad smell, it went across us all….

Little children died or were orphaned. Young married couples with their new little babies died….

People were lost and their names were lost. We were the survivors, and in years to come we re-grouped and relationships were re-confirmed amongst us.

Very special thanks to Linda Rive and the Ara Irititja Archive.

Artwork copyright ©, all text ©.

Paintings courtesy The Sims Dickson Collection and Archive.

This post is adapted from an article that first appeared in Art+Australia journal, 2020. Special thanks to then-editor Edward Colless for recognising the importance of Janet Inyika’s story.

[1] Literally person or us in Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara languages; used by speakers of those languages to describe and identify themselves.